Over the summer — during that fleeting window of time before the Delta variant hit when we believed Covid-19 might be evaporating into a gauzy nightmare of a memory — I interviewed a woman for a story who had lied about her 11-year-old son’s age in order to receive the Covid vaccine, which was then only approved for ages 12 and up.

|

| Sarah Baird (NYT photo) |

"In Kamin’s case, the mental and logistical gymnastics did turn out to be, well, a lot. Kamin’s son’s birthday was in August, so they decided on a fake March birthday to tell the nurse at the medical clinic. (The thought process behind this? Turning the 3 on the vaccine card into an 8 later on would be relatively easy as to not muddle his long-term medical records.) What’s more, as a faux 12-year-old, her son was capable of — and expected to — tell the vaccine administrator his birthdate himself, so Kamin and her husband “drilled” him on his new, false birthday for days leading up to the event and in the car on the way to the appointment."

This astounded me. Is it even ethical? What does that teach the kid? But what confounds me even more is the overwhelming majority of parents in Central and Eastern Kentucky who are choosing not to vaccinate their children at all. This is evident when you look at the data for 5-to-11-year-olds, a group for whom a Covid vaccine was approved in late October, and see that most parents are foregoing the shots entirely for their kids as part of a worrying trend.

We’re looking at the data for fully vaccinated 5-to-11-year-olds as of Sunday, Dec. 26. There’s been quite a bit of reshuffling generally as to what “fully vaccinated” means in the wake of the Omicron variant and the third “booster” dose for adults, but for now — following the guidelines set by the Kentucky Department for Public Health — kids with two shots but no booster are considered completely vaccinated in this breakdown.

A few key takeaways from The Goldenrod's coverage area (Bracken, Harrison, Scott, Franklin, Anderson, Mercer, Boyle, Casey, Taylor, Green, Adair and Cumberland counties and those east of them in Kentucky):

- Only seven counties — Rowan, Franklin, Scott, Woodford, Fayette, Boyle and Jessamine — in the coverage area have a double-digit percentage of 5-to-11-year-olds who have been fully vaccinated. The rest are hovering well below 10 percent.

- Three counties in the area — Clinton, Martin and Robertson — have zero fully vaccinated 5-to-11-year-olds. (A handful have now received the first dose in each of these counties, which is somewhat heartening.)

- The number of fully vaccinated 5-to-11-year-olds in Leslie, Casey, Green, Owsley, Wolfe and Clay Counties is under 100 children, combined.

- Even in Perry County, where 92% (!) of people age 65-74 are fully vaccinated, only 3 percent of 5-to-11-year-olds have received both shots so far.

What do on-the-ground public-health workers think?

Despite several local school districts shuttering early for winter break due to spiking Covid numbers and the Omicron variant causing widespread infection among children nationally — there are currently 1,987 confirmed or suspected pediatric Covid-19 patients hospitalized across the country, according to The Washington Post — rural public-health officials across Central and Eastern Kentucky say there’s little interest in, or urgency from, parents when it comes to vaccinating their vulnerable 5-to-11-year-olds.

“People are still afraid of [the vaccine] even if they get it,” says Kathy Slusher, a community health worker with Kentucky Homeplace in Bell County. “They are afraid to give it to their children. I think as more children get it, more people will come around.”

But what the tipping point might be that will finally push that first, significant wave of families to get their elementary school-aged kids the vaccine remains to be seen in most counties.

Is it striking just the right chord with a public education campaign? Probably not.

Could it be setting up more vaccination sites with dedicated transportation? Doubtful, because public health officials are currently even willing to make house calls (seriously!) to deliver shots to kids.

Or will it come down to the most tragic possibility of all: Parents will have to watch children in their towns fall severely ill—and perhaps die—before they believe in the vaccine for their own offspring?

Greg Brewer of Gateway District Health Department, which serves Rowan, Bath, Menifee, Morgan and Elliot counties, thinks so. “I guess parents haven’t seen enough school-aged kids get sick around them. They just think it’s a runny nose, so it’s not enough to make them concerned and get the vaccine for their kids. That’s the only thing I can think of.”

When I asked if he thought parents were wholly against the vaccine, he said no. “I don’t think they’re antivaxxers, necessarily, but parents are so divided, and they’re just not concerned about their kids getting Covid. They’re going to have to see kids get really sick before they’ll get concerned.”

When I mused that parents might be scared of the vaccine, like Slusher suggested, Brewer didn’t miss a beat. “I don’t think people are scared, because if they were actually scared, they’d get the vaccine. Covid is a lot scarier.”

There was a sense of exasperation in his voice as he rattled off a fairly exhaustive list of ways local health departments in his region had tried to get the vaccine to community members, including those in the 5-11 age group: “We’re making vaccines available any way we can. We’ve talked to schools; set up clinics; we’ll come to your house to vaccinate your family; we’ll do anything you need us to do. We need kids to get the shot. It’s not going to cost you anything, all we need is your arm.”

The school-based vaccine clinic hosted last week in Menifee County, however, drew little participation. “The schools will do anything to get the shots to kids—they’ve been so good about helping with everything like masks and social distancing—but the people just won't do it,” Brewer said.

Health educator Shirley Roberson Daulton with the Lake Cumberland District Health Department agrees: “The urgency isn’t there. I feel like parents, as humans, sometimes listen to all of this misinformation out there. Also, because of events cancelling, we haven’t been able to be out in the community as much to tell people how important it is to get their kids vaccinated. But we’ve been trying to tell every family that comes into the clinic.”

Of course, just like the Anna Karenina principle — all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way — every Central and Eastern Kentucky county struggling with vaccination rates for its youngest eligible citizens has a unique set of hurdles, barriers and misbeliefs to counterbalance before rates among 5-11 year-olds start to climb.

How soon that will be—and how many people will have to face infection, illness or even death before that happens—remains to be seen.

“People are still afraid of [the vaccine] even if they get it,” says Kathy Slusher, a community health worker with Kentucky Homeplace in Bell County. “They are afraid to give it to their children. I think as more children get it, more people will come around.”

|

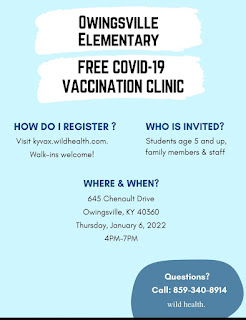

| The Goldenrod's story is illustrated with this notice of a school vaccination clinic. |

Is it striking just the right chord with a public education campaign? Probably not.

Could it be setting up more vaccination sites with dedicated transportation? Doubtful, because public health officials are currently even willing to make house calls (seriously!) to deliver shots to kids.

Or will it come down to the most tragic possibility of all: Parents will have to watch children in their towns fall severely ill—and perhaps die—before they believe in the vaccine for their own offspring?

Greg Brewer of Gateway District Health Department, which serves Rowan, Bath, Menifee, Morgan and Elliot counties, thinks so. “I guess parents haven’t seen enough school-aged kids get sick around them. They just think it’s a runny nose, so it’s not enough to make them concerned and get the vaccine for their kids. That’s the only thing I can think of.”

When I asked if he thought parents were wholly against the vaccine, he said no. “I don’t think they’re antivaxxers, necessarily, but parents are so divided, and they’re just not concerned about their kids getting Covid. They’re going to have to see kids get really sick before they’ll get concerned.”

When I mused that parents might be scared of the vaccine, like Slusher suggested, Brewer didn’t miss a beat. “I don’t think people are scared, because if they were actually scared, they’d get the vaccine. Covid is a lot scarier.”

There was a sense of exasperation in his voice as he rattled off a fairly exhaustive list of ways local health departments in his region had tried to get the vaccine to community members, including those in the 5-11 age group: “We’re making vaccines available any way we can. We’ve talked to schools; set up clinics; we’ll come to your house to vaccinate your family; we’ll do anything you need us to do. We need kids to get the shot. It’s not going to cost you anything, all we need is your arm.”

The school-based vaccine clinic hosted last week in Menifee County, however, drew little participation. “The schools will do anything to get the shots to kids—they’ve been so good about helping with everything like masks and social distancing—but the people just won't do it,” Brewer said.

Health educator Shirley Roberson Daulton with the Lake Cumberland District Health Department agrees: “The urgency isn’t there. I feel like parents, as humans, sometimes listen to all of this misinformation out there. Also, because of events cancelling, we haven’t been able to be out in the community as much to tell people how important it is to get their kids vaccinated. But we’ve been trying to tell every family that comes into the clinic.”

Of course, just like the Anna Karenina principle — all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way — every Central and Eastern Kentucky county struggling with vaccination rates for its youngest eligible citizens has a unique set of hurdles, barriers and misbeliefs to counterbalance before rates among 5-11 year-olds start to climb.

How soon that will be—and how many people will have to face infection, illness or even death before that happens—remains to be seen.

The state health department says 16% of Kentucky children age 5 to 11 are vaccinated, and vaccines are available at primary-care providers and pharmacies in every county.

For a list of the 64 counties sorted by percentage of vaccination, go here.

from KENTUCKY HEALTH NEWS https://ift.tt/3z5bLeJ

0 Response to "With few 5-to-11-year-olds vaccinated against Covid-19, public-health officials say kids will have to get sick to motivate parents-HEALTHYLIVE"

Post a Comment